Introduction

Note from the author: this material is oriented toward vocational and community college students to prepare for the job market. My 1977 plasma discharge tube project showed how electrons drive devices, shaping my electron flow approach.

Understanding introductory chemistry can be helpful when learning electronics for several reasons. This knowledge includes industrial processes from metal plating to making Clorox bleach, understanding solar cell construction, refining aluminum with electricity, and solid-state devices.

This is particularly important in understanding battery charging and discharging. Battery charging is a form of electrolysis.

While electronics deals primarily with the flow of electrons, chemistry deals with atomic and molecular structures that interact with electric currents.

I use electron flow—electrons moving from negative to positive, with potential energy highest at the positive terminal, decreasing to ground. This hybrid approach clarifies electronics, as discussed in my xAI debate.

Electron Flow vs. Holes

Note there is no such thing as holes or positive charges moving through a solid conductor outside P-type material; "experimental evidence exists to prove electrons are free to move, not positive charges, which are fixed in the lattice network of the conductor." Holes are best understood with semiconductors but not, for example, with electrical wiring, capacitors, resistors, etc.

Reference Paul Sharz, Practical Electronic for Inventors.

Note the following for engineering:

Conceptual Holes in Conductors: While there aren't "holes" in the same sense as in semiconductors, in some theoretical discussions or when simplifying complex phenomena, one might use the concept of "holes" to describe electron vacancies in a more general sense, though this is not a standard or accurate depiction for conductors.

Current Direction: In electrical engineering, current flow is usually discussed in terms of "conventional current," which assumes positive charge movement from positive to negative. This convention does not reflect the movement of positive charges in conductors but rather how we model and calculate circuit behavior.

Materials and Semiconductors

Chemistry helps explain why certain materials are conductors, insulators, or semiconductors. Understanding the atomic structure, valence electrons, and bonding properties of metals like copper or aluminum can clarify why they are good conductors.

The behavior of semiconductors, crucial for transistors and diodes, is rooted in chemistry. Doping (adding impurities to a semiconductor like silicon) to create p-type or n-type semiconductors involves chemical processes that affect electron behavior.

Electronics often involve batteries, which are electrochemical cells—understanding how these work, including redox reactions, ion movement, and electrochemical potential, is directly related to chemistry.

Many modern electronic devices incorporate sensors that rely on chemical principles, such as pH sensors, gas sensors, or sensors that detect environmental changes through chemical reactions.

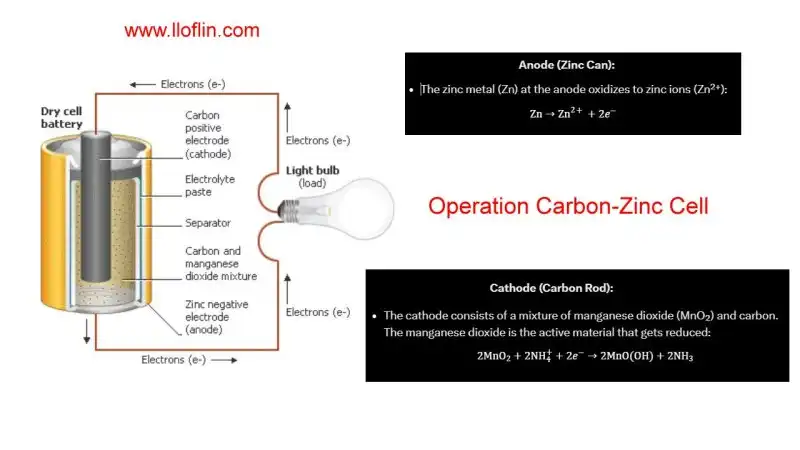

Carbon-Zinc Cell

Carbon-Zinc cell showing anode-cathode and current direction.

The x AI:

"Electrochemistry is the basis of batteries and many industrial processes. Integral to many electronic devices, batteries operate on electrochemical principles, such as battery charging."

From Lewis to the xAI: In a voltaic cell, the current flow is electron flow from negative to positive. The anode-cathode designation is based on the electrochemical cell redox reaction. The source of electrons is oxidation, designated as the anode, but electrically the negative terminal.

The electrode that consumes electrons (from reduction) is designated a cathode. Assuming this was a rechargeable cell during the charging cycle, the oxidation-reduction, thus the anode-cathode designation, is reversed. Is this correct?

From xAI:

Yes, that is correct. During discharge in a voltaic (or galvanic) cell, Oxidation occurs at the anode, which is the negative terminal because it loses electrons; Reduction occurs at the cathode, which is the positive terminal because it gains electrons.

In a carbon-zinc dry cell (also known as a Leclanché cell), the chemical reactions during discharge involve converting chemical energy into electrical energy.

Anode: In a carbon-zinc cell, the zinc (Zn) at the anode undergoes oxidation, losing two electrons to become a zinc ion (Zn²⁺).

The electrons flow through the external circuit, providing the device with electrical current.

Cathode: Composed of manganese dioxide (MnO₂) with carbon (usually graphite) around a carbon rod.

Reaction: During discharge, manganese dioxide is reduced, consuming electrons to form manganese oxides like Mn2O3 or MnOOH. This process involves ammonium ions (NH4+) from the electrolyte (ammonium chloride), producing ammonia (NH3), water, and other by-products rather than stable ammonium hydroxide.

Non-rechargeable batteries (alkaline and traditional carbon-zinc cells) are primary cells. These batteries are designed for single use; once their chemical energy is depleted, they are typically discarded because the chemical reactions within them are not easily reversible.

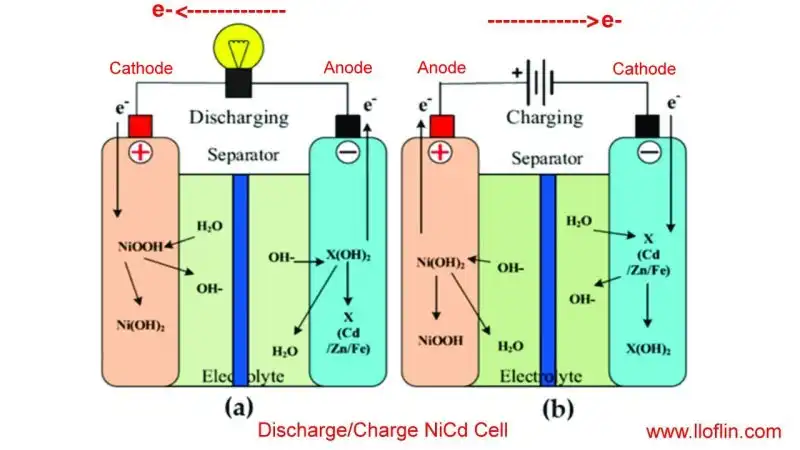

Nickel-Cadmium Cell

Nickel-cadmium cell charge-discharge reactions.

Secondary Batteries: These are rechargeable batteries in which the chemical reactions that occur during discharge can be reversed by applying an external electrical charge, allowing the battery to be reused multiple times.

Reversal of Anode and Cathode Roles During Charging:

Cadmium Electrode: During discharge, this acts as the anode (negative terminal) where oxidation occurs (losing electrons). When charging, this electrode becomes the cathode as it undergoes reduction (gaining electrons).

Nickel Hydroxide Electrode: During discharge, this is the cathode (positive terminal), where reduction occurs (gaining electrons). When charging, it becomes the anode, as oxidation occurs (losing electrons).

Please note that the battery charger's polarity is the same, plus to plus and minus to minus. The charge voltage must be greater than the operating voltage.

This switch in roles ensures that the battery can be recharged by reversing the redox reactions used for discharging.

To summarize:

The anode is the source of electrons where chemical oxidation takes place.

The cathode consumes the electrons from the circuit where chemical reduction takes place.

Chemistry’s Impact on Electronics

Thus, a basic understanding of chemistry can enhance one's grasp of many facets of material science: Why do we use certain materials for different components? How do components interact at the atomic level? How can we prevent or predict failure due to environmental factors?

The depth of chemistry knowledge needed for practical electronics work at the hobbyist or basic professional levels might be limited.

However, as one delves deeper into advanced electronics, materials science, or specialized fields like organic electronics, the interplay between chemistry and electronics becomes more pronounced.

Yes, even introductory chemistry is helpful when learning electronics for several reasons.

Atomic Structure and Electron Shells teach about the structure of atoms, including the number of electrons in different energy levels or shells. Understanding how electrons are arranged (valence electrons) is fundamental to comprehending how current flows in circuits.

Introductory chemistry explains why metals conduct electricity well. This knowledge involves the understanding that metals have free electrons in their outer shells that can move through the material, facilitating electrical conductivity.

Even at a basic level, chemistry introduces the concept of semiconductors, which are crucial in electronics for devices like diodes and transistors. Understanding how doping changes the electrical properties of materials like silicon or germanium can be foundational.

Because of their electrical properties, familiarity with the periodic table can help one understand which elements will be used in electronic components.

Therefore, while electronics can be studied and practiced focusing on its electrical principles alone, a background in introductory chemistry leads to better design, troubleshooting, and innovation.

Explore my training program, circuit projects, or YouTube videos for more.

Share This Article

References

Paul Sharz, Practical Electronics for Inventors, McGraw-Hill Education.

Stephen L. Herman, Electric Circuits, Delmar Cengage Learning.

Personal correspondence with xAI, 2025.

Lewis Loflin’s teaching materials, Bristol Community College, 1980s–1990s.

Related Subjects

- Chemistry for Electronics:

- Why Chemistry is Useful for Learning Electronics

- Electrochemistry and Battery Charger Chemistry

- What is Electrochlorination and Electrolysis?

- Electroplating One Gram of Copper Working Example

- TL431 Battery Charger Voltage Detector Circuits Schematics

- TL431 Sink Mode Constant Current Circuits

- Physics and Chemistry for Electronics:

- Cesium Photo Detectors, Zinc Photocells, and Bandgap Explained

- Cesium Photoelectric Cells

- Is Zinc Photovoltaic?

- Bandgap versus Work Function Key Differences

- How Selenium Rectifiers and Photocells Operate

- Brief Overview of Vacuum Tubes and Circuits

- Basic Review Operation GaAs Photodiodes

- Electronics Education and Careers Defined Six Parts:

- Applied versus Theoretical Science Relation to Electronics

- How does applied science differ from theoretical science?

- Is electronics an applied science?

- What is the difference between electronics and electrical technicians?

- What does "academic ability" really mean in practical terms?

- How does an electronics technician differ from an engineer?

- Electronic Circuits and Applications:

- Electronics and Technology Built at Home Mainpage

- Arduino Constant Current H-Bridge Motor Control

- LM555 Timer Monostable AC Power Phase Control Demo